I was talking yesterday about human history, and so far I’m only up to World War II, so I’m afraid there’s quite a bit left.

In Superman: The Movie, Jor-El tells Superman that he must not interfere with human history, which may have seemed like a good idea in the abstract but is pretty hard to achieve, especially for a guy who can fly and blow things up with his eyes. That kind of thing tends to make a noticeable dent in the arc of history, one way or another.

Superman first encountered this problem just a few years after he was created, when everybody expected him to go and fight on the front lines of World War II, which — given the inherently unstoppable nature of his character — would have led to a limited set of story options.

As we saw in the excerpts from WW2-era Superman comics yesterday, the common American understanding of the war was that there were three or four bad people in the world — Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito and maybe Stalin — and if we could apprehend those individuals and bring them to an international tribunal for justice, the war would be over and everything would be fine. It was basically a battle with a handful of powerful supervillains, and that kind of thing is right up Superman’s street; he could just leap over to Europe and head east, collecting dictators as he went along.

So let’s say that Superman gets his hands on Hitler, and serves him a hot slice of comeuppance. Then what?

It’s not actually a problem if Hitler is defeated in the comics and not in real life, because comics are fictional and nobody expects them to be literally true. The problem is that there’s nowhere else to go with that story. Long-running serialized narrative needs a constant supply of interesting plot points to pursue, and if Superman readers are interested in reading war stories, then you can’t have your main character go and stop the war on page three.

So the creative solution for the comic books, comic strip and radio show was to send Superman out on endless side quests, hunting saboteurs, fifth columnists and Axis-flavored superfoes. That provided him with a constant supply of people to unmask and punch in the face, without the burden of having to make progress in the overall World War II storyline, which they didn’t have any control over.

That strategy was clearly the correct one, and that’s why we still have a Superman. The Golden Age of Comics in the 1940s was full of stars-and-stripes heroes fighting the Axis directly — Captain Flag, Captain Freedom, Miss America, Miss Victory, the Star-Spangled Kid, U.S. Jones, the American Eagle, and the daring duo of Yank & Doodle — and when the war ended, there was nowhere else for them to go. The patriotic characters that survived were Superman and Captain America, and even the Captain had to spend some time in the freezer.

But things got more complicated for Superman in the 1960s, as you can see in this letter published in the Metropolis Mailbag page in Action Comics #338 (June 1966).

Dear Editor: I’m one of Superman’s greatest fans. But there’s one thing about him that bugs me. If he’s so super-powerful, why doesn’t he use his abilities to give our armed forces a hand and end the war in Viet Nam? — Peter Tarsch, St. James, Winnipeg, Canada

Now, the obvious answer to this question is that Superman is fictional and superheroes aren’t real, but the guy comes from Winnipeg and I don’t know what their school curriculum was like. Here’s the editor’s reply:

Superman figures the U.S. is good enough to win this conflict without his help! Besides, warfare involves killing, which is strictly against his moral code. — Ed.

That first sentence is straight out of the World War II playbook, when Superman gave regular pep talks about how the American troops could handle things. The second sentence is more of an innovation, and as we’ll see, a troubling one.

A few years later, the Metropolis Mailbag got a direct request from the troops, which was printed in Superman #214 (March 1969):

I never read any comic mags until I arrived in Viet Nam. It seems that Superman outsells Playboy over here. How about a story for my unit (173rd) where Superman comes to Nam and helps bring this war to a close? I’m presently in the 91st Evacuation Hospital in Tuy Hoa, with a gunshot wound in my right leg. So I’ll have plenty of time to look for your story. — Cpl. Thomas F. Dorf, Tuy Hoa, Viet Nam

This time, the editor’s answer was not a profile in courage.

It takes a while for a story to be written and processed. By the time we could get a tale of Superman in Viet Nam, something may break that will end the war for real. At least, we hope so! — Ed.

As it turned out, there were another six years before the Fall of Saigon, so they didn’t really need to worry about how topical the subject was going to be. But strangely, just two months later, they actually did run a story that did exactly what Cpl. Dorf asked for.

The story is called “The Soldier of Steel”, and it was published in Superman #216 in May 1969.

The cover shows Superman on the front lines, surrounded by the dead and wounded, as he faces down an enormous figure looming out of the fog. Taking off an army uniform, he thinks: “My orders are to destroy that G.I. giant! The only way to save our platoon is to break my code against killing!” So we’ll see how that goes.

The story begins with teen rebel Johnny Morely, an American G.I. stationed in Anytown, Vietnam, losing his goddamned mind. As he breaks from formation and runs off in no particular direction, there’s a little chorus of comrades who discuss the situation. We’re going to see a lot of that technique in this story — a little intel from the band of brothers, chattering away whenever the action gets heavy.

“Johnny! Johnny — come back!”

“The poor kid’s flippin’!”

“Yeah — he broke under the shelling!”

So this is a very different direction than the glib “America can handle this without Superman’s help” concept. As we’ll see, this story is very confused about what it wants to say, and it’s interesting that it opens with a graphic depiction of the mental suffering of an American soldier.

And then it gets weird.

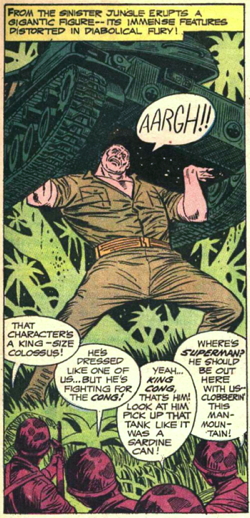

“From the sinister jungle erupts a gigantic figure,” says the caption, “its immense features distorted in diabolical fury!” And here he is, the G.I. giant, picking up a tank and trying to figure out what he’s going to do with it.

The shocked soldiers exclaim:

“That character’s a king-size colossus!”

“He’s dressed like one of us… but he’s fighting for the Cong!”

“Yeah… King Cong, that’s him! Look at him pick up that tank like it was a sardine can!”

“Where’s Superman? He should be out here with us — clobberin’ this man-mountain!”

So that’s an earnest little spray of DC dialogue that establishes how this is going to play out, tone-wise. “Look at him pick up that tank like it was a sardine can!” is not a sentence that occurs in nature. In the next panel, they try to shoot the monster, but find that he’s invulnerable: “Our shots are rattlin’ off him like popcorn!” That’s how everybody talks.

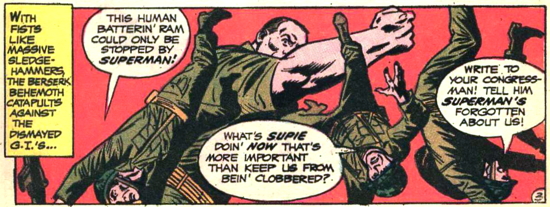

Even during an action shot, the characters get to hang in midair and have a conversation:

“This human batterin’ ram could only be stopped by Superman!”

“What’s Supie doin’ now that’s more important than to keep us bein’ clobbered?”

“Write to your congressman! Tell him Superman’s forgotten about us!”

The soldiers in this comic sound like Huey, Dewey and Louie; they always have the same opinions about everything. They also use the word “clobbering” twice on the same page, which is apparently the DC-approved term for “killing”.

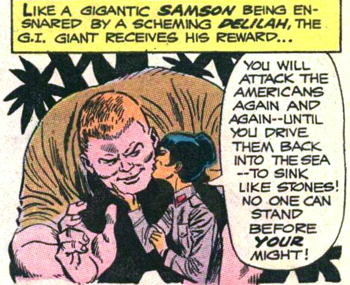

And then, get a load of this. When the clobbering is complete, the giant stomps off through the jungle to reconnoiter with his trainer: Dr. Han, a Vietnamese dragon lady.

If you’re not familiar, “dragon lady” is a regrettable Asian stereotype that I hope by now has passed from the earth. The dragon lady is a powerful, manipulative woman who uses a combination of fierce intelligence, sex appeal and ruthlessness in order to seduce and then destroy her enemies. Dragon ladies were all over the place in mid-20th century adventure fiction. The term was coined in 1934 for Milt Caniff’s newspaper strip Terry and the Pirates, which everybody says is very important if you’re interested in the history of comic strips, but somehow I’ve never gotten around to it.

It’s all part of the Yellow Peril, a racist ideology that played a distressingly large role in the development of late 19th and early 20th century adventure fiction. Fu Manchu is the best-remembered Yellow Peril villain, and unfortunate analogues show up all over the place, including stuff that I like: Flash Gordon (Ming the Merciless), Doctor Who (the Celestial Toymaker and Weng-Chiang), Iron Man (the Mandarin) and Batman (Ra’s al Ghul).

The basic idea in Yellow Peril fiction is that Asian people are supposed to be short, cowardly, physically weak, and essentially identical — and in order to make up for these physical shortcomings, they’re born connivers. They lie, they make complicated plots, and there are tons of them, so they can overwhelm the physically superior white heroes through sheer numbers. Asian people in Yellow Peril fiction are basically reptilian, with claw-like fingernails and sharp, poisonous fangs.

The common words to describe Yellow Peril characters have lots of hissing S sounds, like sneaky, scheming, sinister and inscrutable. We’ve already seen the word “sinister” pop up in this story; stay tuned for a couple more from the list.

And hey, here’s one now: “Like a gigantic Samson being ensnared by a scheming Delilah,” says the caption, “the G.I. giant receives his reward.”

The reward is a kiss from the dragon lady, obviously; she’s managed to drug the shell-shocked Johnny and turn him into her monstrous hypnotized love slave. “You will attack the Americans again and again, until you drive them back into the sea — to sink like stones!” she says. That’s dragon ladies for you.

But it looks like Corporal Dorf’s Metropolis Mailbag query got rerouted to the desk of Clark (Superman) Kent, who reads it with X-ray vision rather than opening it like a normal person. “I don’t have to open the letters to read their contents!” he humblebrags. “My X-ray vision tells me they’re all the same… complaints against Superman for not helping the troops in Vietnam!”

The caption describes this as “a rising tide of G.I. mail”, which makes me wonder how many letters the DC offices actually received.

Clark decides to do something about it, so he goes to Perry with a story idea: “I’d like to go to Vietnam — mingle with the troops in the front lines — find out about their beef with Superman! Not as a reporter… as a fellow soldier! But I don’t like killing, so I’ll go as a medic!”

Perry thinks that this is a great idea, but I have my doubts. Does the Army actually take requests like this? It sounds to me like they’re playing a practical joke on soldiers, inserting random people into their unit under false pretenses. I can’t imagine that’s good for morale; it’s no wonder we’re having a tough time with the war.

I wrote yesterday about the 1941 comic strip storyline that established why Clark (Superman) Kent stayed home in Metropolis, rather than enlisting in the Army: he did well in the physical, but flunked the eye exam, because he accidentally used his X-ray vision to read the eyechart from the exam room next door.

This story has a similar sequence, which they play for laughs. It begins with the doctor shocked to hear Clark’s “super-heatbeat” through his stethoscope, and Clark has to use his “super-ventriloquistic powers” to convince the doctor that what he heard was thunder outside.

And then they do a riff on the eye exam scene, which I think is probably an intentional callback. Clark reads a string of letters off the eyechart, and the doctor says, “I’ll have to disqualify you! You’re almost blind!” — a paraphrase of what the doctor told him in 1941. The gag in this version is that he was reading the tiny “Printed by the Acme Press” line at the bottom of the chart, because Superman is a smartass.

So it’s next stop Saigon, as a disguised Superman travels to the front lines on a transport plane with his new unit. Down below, “pitiless enemy eyes” are watching the American plane approach, so we’re really just going full-on Yellow Peril today. “The unwary Yankees do not know we have hidden anti-aircraft guns here!” says the scheming Vietnamese soldier below, and then lets loose with a charge that blows a hole in Clark’s plane.

What happens next is extremely complex. A soldier falls out of the plane, and Clark thinks, “I can’t let him die! I must take the chance that no one will see me using my suction breath in this confusion!”

He takes the chance, and guess what, it works. “What luck!” the rescued soldier says. “An updraft must’ve yanked me back inside!” which is so bizarrely slap-happy that I can barely believe it. You’re on a plane that’s currently crashing. Why would you consider yourself lucky in this moment? How would an updraft do that? For that matter, how does “suction breath” work? So many questions.

But the most curious part of that sequence is the line “I can’t let him die!” which opens up a whole line of thought.

This is a war. People are using weapons, and soldiers die. There are other soldiers dying all over the place. When Clark says “I can’t let him die,” what he means is that he can’t let the one soldier die who happens to be in front of him, right now.

When you think about this, it demonstrates how arbitrary Superman’s moral code is. At any given moment, there are countless numbers of innocent people who could use his help all over the world, and he helps the ones that catch his eye. The people on the plane that got shot down yesterday had to deal with it themselves, but this guy is standing in front of him, so all of a sudden it’s a moral imperative to help him.

I know, I’m being cynical, but Vietnam does that to people. I may have pissed off Superman; in this panel, he’s giving me the stink-eye like you wouldn’t believe. Clark managed to jump out, turn into Superman and catch the plane before it hit the ground, and I’m not being very appreciative.

The soldiers jump out, guns blazing, and there’s another snatch of dialogue from a faceless foursome.

“Look! It’s Superman!”

“Who said he wouldn’t come out here to help us?”

“A lot of good that’ll do — now!”

“Yeah! We’ll be cold meat on the table for those guns before we can dig foxholes for cover!”

I don’t know what to do with these little barbershop quartets that spring up throughout the book; they seem so cheerful, even when they’re about to be clobbered.

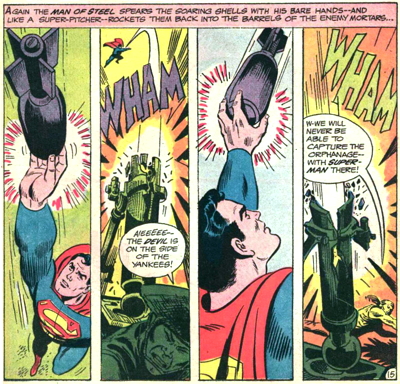

To help out, Superman digs them a trench at superspeed, and then protects them by playing catch with the incoming artillery fire. There’s another happy chorus, including a couple of baseball references that I don’t entirely understand.

“Wow! Look at Supie snarin’ those TNT Texas Leaguers!”

“He could teach baseball bigs a few things about fielding!”

“This is better than any U.S.O. show he could put on!”

And I don’t know, maybe that’s exactly what soldiers sound like on the front lines. I can’t prove that they don’t.

Now, the key to Superman’s intervention plan is that he’ll touch machines and objects, but not people. This is what he does: “Instantly, Superman leaps at the tanks, and with super-karate blows, cleaves them open like bursting cans.”

Super-karate blows.

You know, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen Superman practice his super-karate before; I wonder why that’s coming up now. He’s certainly turning those tanks into chop suey; it must be one of those ancient Chinese secrets.

Once he’s taken care of the tanks, the cheerful soldiers cry:

“C’mon, guys! Let’s back Superman up!”

“Thanks for mindin’ the store while we got organized, pal!”

“We’ll take care of these new customers!”

“They’re comin’ on like it was a fire sale!”

“If it’s scorched goods they want… we’ll give ’em plenty!”

And then they go and shoot a bunch of dudes, which makes me wonder about this amazing moral code that Superman’s got. He says that he won’t kill — I guess those tanks he’s been cleaving were all radio-controlled — but he’s certaintly facilitating the killing that’s happening just off-panel.

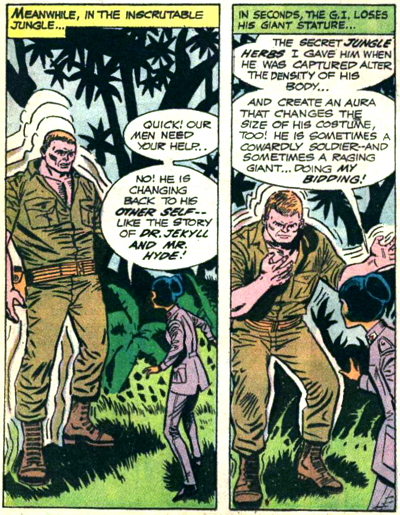

Then the caption says “meanwhile, in the inscrutable jungle,” because of course it fucking does. The giant has gotten tired of clobbering things and returns to Dr. Han, who watches him transform back into his ordinary shape.

“The secret jungle herbs I gave him when he was captured alter the density of his body,” says the scientist, “and create an aura that changes the size of his costume, too! He is sometimes a cowardly soldier — and sometimes a raging giant, doing my bidding!” Good to know.

Confused, Johnny runs off into the jungle, and Dr. Han sneers, “He’ll return to his his unit now… to burst forth like a booby trap, when the herbs make him grow again! Then he will destroy his own comrades!” This is all extremely wily.

Johnny returns to his unit, apparently recovered from his shell shock; now he’s all smiles. He quickly befriends Clark, and invites him on a field trip: “All the guys are visiting orphanages, taking gifts of K-rations and candy! I’d sure like you to come with me!”

Now, I don’t know enough about the Vietnam War to know if this is a reference to something that American troops actually did; I know about the massacres, but not the candy distribution programs. Presumably, these kids are orphans because American troops killed their parents, so I’m not sure why they look so happy, but I guess everyone likes candy.

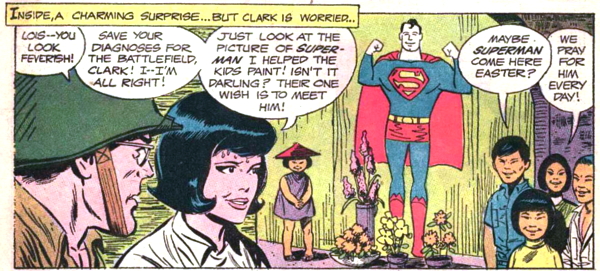

At the orphanage, Clark finds Lois, who’s also managed to book an investigative jungle vacation, and she’s been helping the children the only way she knows how, which is to obsess over Superman. “Just look at the picture of Superman I helped the kids paint!” she says. “Isn’t it darling? Their one wish is to meet him!” Well, maybe not their one wish — I bet having their parents alive is on that list — but Superman is probably in the top two.

“Maybe Superman come here Easter?” a little orange-faced orphan says, inscrutably. “We pray for him every day!” Weird.

Then the scheming Vietnamese start attacking the orphanage for some reason, so Clark changes clothes and catches all the bombs, throwing them back at the enemy mortars.

“Aieeeee — the Devil is on the side of the Yankees!” says the Vietcong rep. “We will never be able to capture the orphanage — with Superman there!” I don’t know why the Vietcong are trying to capture an orphanage with mortar shells; they just are. They’re really struggling to come up with ways to make Superman into the good guy.

There’s also a side plot about Lois collapsing from jungle fever, which I don’t want to talk about. “Miss Lois very sick!” the children say. “She fall down!” Jesus Christ.

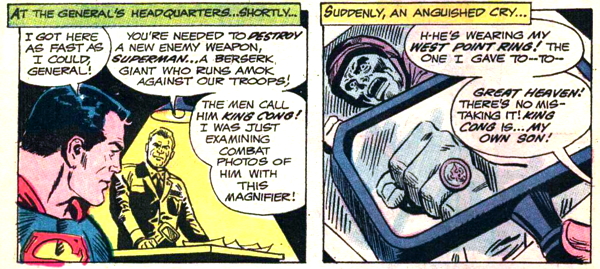

Okay, are you ready for this to get even more perplexing? Here we go. Superman’s flying around the battle zone when he hears an urgent appeal over the radio: “General Morely calling all units! If you see Superman — notify him to come to my headquarters immediately! It’s urgent!”

So that brings up the confusing question of Superman’s relationship with the armed forces. He’s not here as a part of the military; he’s a vigilante, a rogue agent acting on his own. In 1941, he didn’t try to enlist in the army as Superman; he presented himself at the recruiting office as Clark Kent. But here he is, showing up on request, saying, “I got here as fast as I could, General!”

And the General just goes straight into giving him instructions: “You’re needed to destroy a new enemy weapon, Superman… a berserk giant who runs amok against our troops!” He was doing that anyway.

Then General Morely looks at combat photos of the giant with a magnifying glass, and discovers: “H-he’s wearing my West Point ring! The one I gave to — to — Great heaven! There’s no mistaking it! King Cong is… my own son!”

There’s your big plot twist: the General’s son is little Johnny Morely, the shell-shock kid, who’s under the intermittent control of Dr. Han. The General considers the situation, and issues the following statement: “I don’t know what has turned him into a monster! But he is a threat to countless American lives! My — my order still stands! Destroy him — before he can do any more harm!” I don’t know why Superman is taking orders, but he seems to agree.

Then it’s back to Dr. Han, who activates Johnny’s jungle herbs by kissing him. “Holy mackerel! Has this Viet dish flipped for me?” thinks Johnny. And then he turns into a monster.

So here’s an interesting fact about the war: American tanks have people inside them, who are concerned about being beaten to death by the super-powered monster bent on their destruction. That’s just a fact that I know about American tanks.

Okay, we’re almost done. Superman flies out to battle, and a soldier shouts happily, “Now our own ‘secret weapon’ is gonna clobber King Cong!”

But before they can get down to serious clobbering, General Morely shouts to the monster, “Johnny! Stop! What’s happened to you?” And Johnny recognizes him, obviously, because that’s how fiction works.

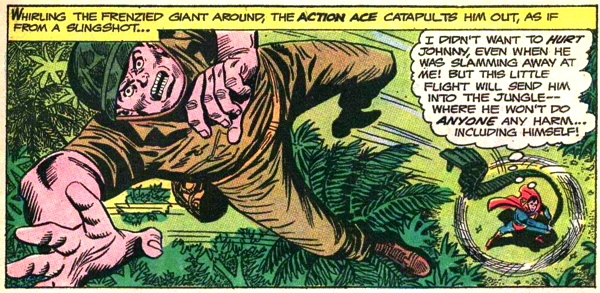

Superman takes the opportunity to hurl Johnny off into the distance, where he can turn back into a person and get his life together.

And once again, we see our hero messing around with tanks, which saves the day without killing anybody, apparently.

But then Johnny comes running out of the jungle — his mind once more his own — and he just starts blazing away happily at the Vietcong troops.

“Superman!” cries General Morely, father of the year. “Help my son… before the Vietcong fire cuts him to pieces!”

“No, general!” Superman responds. “Give him a chance to fight back his own fears, or he’ll always be a coward!”

So that’s morally incoherent, on a drastic scale. Superman says that he doesn’t want to kill, but he specifically holds himself back from stopping the slaughter of the Vietcong, because he wants Johnny to grow up and become a proper gun-toting, Cong-murdering soldier. I don’t know how you get your head around that.

But here’s the happy finish — Dr. Han and the surviving Vietcong are taken away as prisoners, and Johnny gives the fiendish doctor a sarcastic smooch on the cheek as she passes by. “Say, I remember you now,” he mocks. “Thanks for making me super, so I could clobber your Cong buddies!” I guess we’re still calling it clobbering.

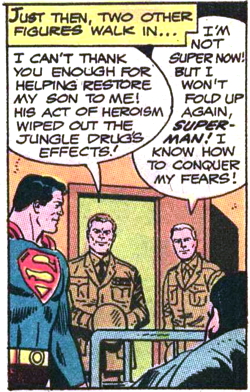

More happy endings: Lois recovers from her jungle fever, Johnny’s heroism has wiped out the jungle drug’s effects, and now Johnny knows how to conquer his fears and kill the VC. Everything’s working out!

And here’s the big finish: Superman putting on a show for the troops, creating a merry-go-round of happy Vietnamese orphans singing “Here Comes Peter Cottontail” with a puff of his super-breath, because it’s Easter, and I don’t know. Maybe Jor-El was right, about the human history. It’s probably better if we just leave it where it is, and go find something else to interfere with.

Tomorrow:

The worst scene that isn’t in the movie

1.65: You’re Doing It Wrong

— Danny Horn

“When you think about this, it demonstrates how arbitrary Superman’s moral code is. At any given moment, there are countless numbers of innocent people who could use his help all over the world, and he helps the ones that catch his eye.”

I often think of something Francois Mitterand said. Asked what he found it most difficult to achieve as president of France, Mitterand replied “Indifference.” He knew that a vast number of people needed help he was in a position to give, but that unless he focused on a few at a time he would be of no use to anyone. So he had to choose the beneficiaries of his intervention indifferent to his own personal preferences, and to go on with his work knowing that there were many people for whom he had not done anything who would have been as worthy as those for whom he did much.

So far, so obvious. We can perhaps accept that presidents of France have a finite ability to do good in the world, and deal with them as representatives of a world in which all moral questions are ambiguous. But moral ambiguity isn’t fun in the way that Superman is fun. Put him into World War Two, and you can have him arrest Hitler and his associates, who have the advantage of being clearly bad. After you’ve done that, you quickly run out of situations in which an unlimited capacity for violent physical action can do anything but elevate one evil over another. Put him in the Vietnam War, and you’re in that situation straight off. That may be a fruitful story environment for Doctor Manhattan or The Plutonian, but to see Superman dealing with that is just depressing.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Exactly. Superman is supposed to be this shining moral absolute, but war is nothing but blood-soaked nuance and depressing mitigating circumstance.

If Superman had been around for the American civil war, would it have been moral for him to stop the war altogether? Wouldn’t that have been giving a big ol’ Kryptonian okay to slavery?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“The secret jungle herbs I gave him when he was captured alter the density of his body,” says the scientist, “and create an aura that changes the size of his costume, too!”

Well, that’s handy, but why his clothes shrank and grew with him was not really the most serious problem I had with this.

Clark would have been very useful censoring letters in WW2 if he doesn’t even need to open the envelope. He could have been helpful in the Dead Letter Office of the Post Office, too, reuniting errant love letters and lost birthday cards with their intended recipients. But that would make for a less action-filled, sweeter and more heart-warming, Superman.

Christopher Reeve would still have been perfect playing him.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I guess I’m wondering how our troops in Viet Nam responded to the story? Certainly it was probably a mindless diversion/entertainment for some — just to get the mind off of the real hell of war — and better than doing drugs – pot, etc. – that some of our troops were doing back then. Of course, other troops probably had a lot more pressing concerns at this time – just trying to take things one day or one moment at a time.

Instead of having Clark (Superman) enlist or try to enlist, I think even during Nam there may have been occasions where reporters/journalists were “embedded” with the troops – I do know that practice of having “embedded” journalists really did happen during the post-9/11 Global War on Terror (GWOT) in the actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. It may have worked better as an excuse to have Clark cover the war for the Daily Planet, rather than to have him enlist as a medic.

Technically, if he did enlist, then yes, he presumably could take orders from a general. But then that raises a legal question – was it Clark who enlisted or Superman? Was Superman given some kind of honorary rank? Even if Superman was a special civilian contractor, he technically would have been subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, assuming the UCMJ was around during Viet Nam and that this precedent about civilian contractors being subject to UCMJ was in effect back then? Certainly our “hired” civilian contractors/mercenaries during post-9/11 – such as the infamous “Blackwater” – were technically subject to the UCMJ.

I was born in the early 60’s, so I was pretty young during Viet Nam. My aunt’s brother served in the Navy in Nam and was an alcoholic due to untreated PTSD, I believe.

(BTW, I was a paralegal in the Air National Guard for 11 years out of my 20 total Guard years. I did an 11-month Title 10 active duty tour post-9/11 [including a short overseas tour in Saudi], so I know a few things about that time.)

I do agree though that this particular Superman story raises a lot of logical questions and cringe-worthy moments, especially the racist stereotyping.

As a side note on World War II, and a pre-Superman George Reeves, I just saw “So Proudly We Hail” (1943) at Internet Archive (at https://archive.org/details/Dick458_gmx_302/302-2.mp4). I was blown away and very surprised to see a very earnest, sincere and charming George Reeves play leading man to Claudette Colbert and hold his own!!!! (I knew George Reeves was in this film, but I had no idea he was the male lead!) And he got 4th billing behind the big female stars – Claudette, Paulette Goddard, and Virginia Lake. (It’s so too bad that George’s Superman TV role typecast him – I think he was a fine actor – and his humor/twinkle and charm just leaped off of any screen he was on.)

Anyhow, your discussion of war and Superman sort of reminded me of this film — “So Proudly We Hail” is actually somewhat surprisingly realistic – about nurses in Bataan. The film is actually amazing – well-acted, and Claudette and an unglamorous Virginia Lake — well, you’ll have to see it for yourself. It’s one of the hidden gems on the Internet Archive. (Sorry for this long post…)

LikeLiked by 3 people

Certainly there were reporters in Vietnam, though I don’t know if they were embedded as they were later. The late anchor, Peter Jennings, reported from Vietnam and even my local tv station sent a newsman there as a war correspondent.

I was wondering, too, how this story would have been viewed by the soldiers. It’s an odd story and I’m not sure how they would feel. Maybe they’d laugh at it. Somehow I don’t think it’s what Cpl. Dorf had in mind.

Obviously, Superman couldn’t end the Vietnam war or World War 2, but maybe what the soldiers wanted was a wish-fulfilling fantasy, some hope that by some miracle, it would be over soon. Instead they got, “Don’t let fear make you a coward. Or a danger to your fellow soldiers. You can do this!” And then Superman goes back to the US and they go back to the war.

There have been a lot of “Let’s Kill Hitler” stories and, recently, Tarantino and “Supernatural” do actually kill him. It can’t actually change anything; history is history. But maybe the point is that at least there’s some catharsis. Evil is eliminated. Lives are saved. Yes, it’s violent, but they have their own moral code and at least it’s consistent.

LikeLike

What gets me about the Yellow Peril garbage is that they use equally stereotyped kids to show that we aren’t the bad guys because we understand how cute those little orphans are and give them candy!

So, when those traumatized children hit puberty, do they suddenly become The Enemy? What’s the cutoff point?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on their outfits, I’m guessing that when their failure to age normally made things dicey for Yank and Doodle they disappeared for a few years and came back as their grandsons Ace and Gary (whose “Fortress of Privacy”, by the way, has a cocktail-serving houseboy).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Having done some Googling, I want to point out that when I insinuated that Yank and Doodle became The Ambiguously Gay Duo I was unaware that Y & D were a) underage (that’s why they became costumed superheros — they couldn’t enlist), and b) were identical twin brothers Rick and Dick, sons of the 2nd Black Owl (who, despite the name, is not a Watchmen character). So…unintentional ewwww on both counts. Although depending on how you think TAGD has aged I still recommend the Fortress of Privacy episode on YouTube, as well as the live action sketch with a surprisingly limber Jimmy Fallon as one of the Duo…

LikeLike

“General Morely” is a reference to William Westmoreland, a West Point graduate who commanded US forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968.

Blame Stan Lee for all that silly wise-ass background dialogue. He didn’t write the story of course but he definitely inspired the tone. By 1969 DC was very aware of the growing Marvel phenomenon and struggling with ways to deal with it. Imitating Lee’s sarcastic patter was one such (ill-advised) way.

Milton Caniff’s exalted reputation in comics history is very well deserved and his work worth exploring. On a related note, a study of how whites and blacks were portrayed in Asian popular culture of the 1930s and ’40s would be very interesting to read, if one exists.

On the broader topic of Superman interfering with human affairs, DC took a brief stab at addressing the issue in 1972. The big guy gets hauled up before Green Lantern’s bosses, the Guardians of the Universe, who lecture him about being a busybody and making people dependent on him. This was part of a short-lived attempt in the early 1970s to make the character more realistic, which I’ve written about earlier. The hand-wringing was quickly forgotten, like most of the other changes.

Here’s a link to the issue. It’s got a great teeth-gritting, fist-clenching cover by Curt Swan, demonstrating that Swan had taken notice of the dramatic innovations introduced by Neal Adams.

https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/Superman_Vol_1_247

LikeLiked by 3 people

One thing I love about the Barbershop Patter Quartet is how insanely dated the slang is. Soldiers did not go around saying things like “clobberin'”, they used language foul enough to make a pirate’s parrot blush and ethnic slurs no sane publication would let see the light of day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right, this is clearly Stan Lee patter. I can’t believe I missed that; thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice to know Superman is against killing for his own purposes (which makes sense because otherwise there’s no way to justify his not stomping Hitler into a pancake) but it’s totally okay for Johnny to mow through hundreds of Viet Cong troops.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Not only do they describe a shell-shocked soldier as cowardly, their cure is to give him a gun and have him shoot people. And then he’s all better! Shell-shock was common in WW1. There’s no excuse for this amount of ignorance.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Moe: Well, let’s see now, uh, time was you sent a boy off to war. Shooting a man’d fix ’em right up. But there’s not even any wars no more, [sarcastically] thank you very much, Warren Christopher!

The Simpsons #168, “Homer’s Phobia” – 1997

LikeLiked by 1 person